Non-Euclidean Geometry

The idea of geometry was developed by Euclid around 300 BC, when he wrote his

famous book about geometry, called The Elements. In the book, he starts

with 5 main postulates, or assumptions, and from these, he derives all of the

other theorems of geometry. The postulates are as follows:

|

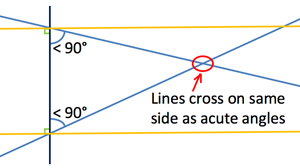

| Illustration of Fifth Postulate

|

- Given two points, there is a straight line that joins them.

- A straight line segment can be prolonged indefinitely.

- A circle can be constructed when a point for its centre and a distance for its radius are given.

- All right angles are equal.

- If a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, will meet on that side on which the angles are less than the two right angles. [1]

The fifth postulate is clearly more complicated than the other four, and, over

the years, many mathematicians were upset by this fact, believing that the

fifth postulate should, in some way, be possible to derive from the first four.

However, in attempting to do this, they just ended up coming up with several

equivalent postulates. A few are as follows:

- Given a line and a point not on the line, it is possible to draw exactly one line through the given point parallel to the line.

- To each triangle, there exists a similar triangle of arbitrary magnitude.

- The sum of the angles of a triangle is equal to two right angles (180 degrees). [2]

Thousands of years after Euclid introduced the problem, nobody had yet come up

with a proof of the fifth postulate; instead they had just come up with many

postulates that were equivalent. By the mid-nineteenth century, mathematicians

(Gauss, Bolyai, Lobachevsky, Reimann and Klein, to name just a few) began to

explore alternative geometries, where this fifth postulate was not true.

|

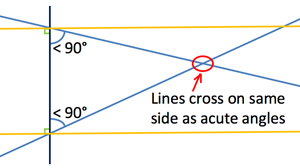

| Constant Negative Curvature

|

Euclidean geometry assumes that there is a unique parallel line passing through

a specific point; any other line will cross the original line at some point.

However, you could imagine a geometry where there are many lines through a

given point that never pass through the original line. This type of geometry is

called hyperbolic geometry.

|

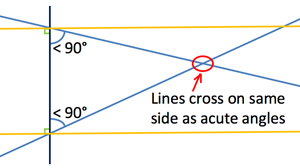

| Constant Positive Curvature

|

Conversely, a geometry could exist where it is impossible to draw a line that

never passes through another line; this type of geometry is called elliptical.

Hyperbolic geometry is a mathematical description of space of negative

curvature; elliptical geometry describes space of positive curvature.

2-dimensional

space of constant positive curvature is mathematically equivalent to the

surface of a sphere in 3 dimensions; the representation of 2-dimensional space

of constant negative curvature in 3-dimensional space could be imagined as

looking something like a saddle. Because there are only three options (multiple

lines that never cross the original, one line that never crosses the original,

and no lines that never cross the original), there are only three basic types

of

geometry possible (hyperbolic, Euclidean, and elliptical, respectively); all

other types are combinations of these three.

The CurvedLand applet models an example of elliptical geometry; in the applet,

you can see that any line you draw will eventually cross all other lines that

you draw.

Curved space was simply a mathematical idea until Einstein developed his

general theory of relativity in 1915 [3]. This theory posited that, instead of

being a force, gravity was the result of the curvature of space and time.

Finally, the idea of curved space, or non-Euclidean geometry, had a real-world

application. Although general relativity's

predictions only differed from the classical model of gravity by a small

amount for most observable situations, it accounted for some unexplained

inconsistencies perfectly; for example, a small deviation in Mercury's

orbit was not explained by the classical model of gravity, but was perfectly

explained by general relativity. Another consequence of general relativity,

called gravitational lensing, was observed in 1919 [3], shortly after the

theory was proposed; this effect involves the bending of light from a distant

star as it passes by a massive object, and is discussed in more detail in this

article about gravitational lensing published by NASA, and

in this

video on

YouTube, produced

as part of the Cosmic Cinema series by the Max Planck Institute of

Astrophysics. These observations support the validity of general relativity,

and the actual existence of curved space-time, giving tangible reasons why we

should try to better understand non-Euclidean geometry.

Resources

- Euclidean Geometry. (2009). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved November 2, 2009 from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/194901/Euclidean-geometry

- O'Connor, J.J. & Robertson, E.F. (1996). Non-Euclidean geometry. Retrieved November 3, 2009 from http://www.gap-system.org/~history/HistTopics/Non-Euclidean_geometry.html

- Lightman, A. (2005). Relativity and the Cosmos. Einstein's Big Idea Homepage. NOVA, PBS. Retrieved November 7, 2009 from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/einstein/relativity/

Close Window

Copyright (C) 2010 Stephanie Erickson, Gary Felder

Terms and Conditions of Use