Active Learning Resources for

Modern Physics

by Gary N. Felder and Kenny M. Felder

"The only way a skill is developed—skiing, cooking, writing, critical thinking, or solving thermodynamics problems—is practice: trying something, seeing how well or poorly it works, reflecting on how to do it differently, then trying it again and seeing if it works better."-Richard Felder

The practice of "active learning" uses student-centered activities in class to encourage them to adopt an engaged and reflective attitude. See www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1319030111 for a general introduction to active learning, and a list of relevant publications.

Research has validated the success of this approach for student understanding and retention, but as an instructor you may have found that supporting students in active learning requires a lot of work. Traditional textbooks and other available resources can be at cross-purposes with active learning and require not just your own creativity but many long hours to rework these materials into an active form. The materials that have been developed to support active learning are mostly at the introductory level.

We have two types of active learning for Modern Physics: "Discovery Exercises" designed to introduce topics, and "Active Reading Exercises" designed to check and prompt student thinking in the middle of presenting topics. You are free to download them and use them. Scroll down for more detailed descriptions of Discovery Exercises and Active Reading Exercises.

CLICK HERE FOR DISCOVERY EXERCISES

CLICK HERE FOR ACTIVE READING EXERCISES

These exercises are all incorporated in our Modern Physics textbook. Click here for information about the book.

Discovery Exercises

An "exercise" is not the same as a problem. A Discovery Exercise is designed to be done before students learn a topic, in order to help prepare them for it; problems are generally assigned after a topic has been discussed in class, to give the students practice and/or deepen their understanding.

A "discovery exercise" steps through a technique. In the Discovery Exercise on time dilation, a student steps through some simple Galilean calculations to find the speed of a light beam in two different reference frames. This exercise leads students to the classical conclusion that light beams go at different speeds in different reference frames; more importantly, the students themselves put together a seemingly incontrovertible argument showing that light must go at different speeds in different reference frames. So when they read the section or hear in lecture that Einstein's posulated that the speed of light is constant, they are clear on why that postulate can't be easily incorporated into Newtonian physics.

Frequently Asked Questions About Discovery Exercises

At home or in class? Alone or in groups?

Mix it up. See what works for you. We sometimes assign them as homework due on the day we are going to cover the material, and sometimes as an in-class exercise to begin the lecture. You can have students do them individually or in groups, or a mix of the two. One professor we spoke to starts them in class, and then has her students finish them at home—an approach we never even thought of. You will probably keep your students' interest better if you vary your approach.

Do I need to assign all the exercises?

No. If you are uncomfortable with the process, you may want to try only one or two. We hope you will find them easy to use and valuable, and over time you will use them more, but you will probably never use them all.

How long do they take?

Some are five minutes or less. Very few of them should take the students more than 20-30 minutes, and most should take 15 minutes or less.

That was all pretty noncommittal. Do you have any solid advice at all?

Actually, we do. First, we hope you will use at least some of the exercises, because we believe they contribute a valuable part of the learning process. Second, exercises should almost always be used before you introduce a particular topic—not as a follow-up. You can start your lecture by taking questions and finding out where the students got stuck.

Active Reading Exercises

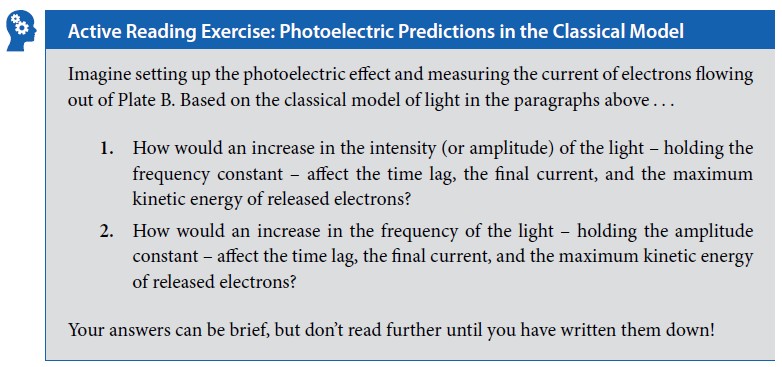

In our textbook, the following appears in the middle of the “photoelectric effect” explanation. Before this exercise we discuss the experimental setup, and the classical picture of an electron gradually absorbing energy from an electromagnetic wave.

If you are using our textbook, some motivated students reading the text before class will pause to try these exercises before reading on. Doing so will greatly improve their understanding and retention of the material. But many students will not do that, and their first introduction to the material will be in your lectures.

So whether or not you are using our book, we would love you to try, just with one or two of these, pausing your lecture at that point. Put a slide up with those questions. Give the students one minute to think about these questions on their own, and then another minute to compare and discuss answers with their neighbors. Research shows that one or two such interruptions, lasting no more than 1-2 minutes each, vastly improve student retention of a 50-minute lecture.

What then? In some cases (as in the example above), the answer is vital to the next steps in the lecture. So you might pick up your lecture by polling the students about their responses and then discussing the right answer. In other cases, the answer to the Active Reading Exercise isn't vital at that point and you can leave it for them to think about as you move on.

- Click here to download a PDF with all the Active Reading Exercises in the book

- Click here to view a list of solutions to selected Active Reading Exercises (specifically, all the ones that are not answered in the textbook itself)

|

|

Click here for the home page for the book, http://www.felderbooks.com/modernphysics. |

|

If you have questions, we would love to hear from you. Click here to email the authors at GFelder@Smith.edu. |